Concentrated stock positions can be the source of considerable wealth creation. Executives who own or run companies are often rewarded with company stock or stock options, and their personal success is typically intertwined with that of the business. As is so often the case, however, this success does not come without its drawbacks. When that wealth is achieved, it is by definition highly concentrated and thus particularly vulnerable to downside risk. A key question for many investors becomes: what can they do about it?

Concentration is somewhat of a moving target for financial professionals. For many, a position is considered concentrated when it makes up more than 5% of an investor’s liquid portfolio. However, the threshold may be higher (10% or 15% perhaps) if the concentration comes from two or three similar securities.

The implications of the concentration may also vary. For example, it could be that the investor’s future financial success is highly dependent on the long-term stability of the underlying stock price. Conversely, a concentrated position might constitute only a component of a family’s assets, making their issue more one of wealth transfer and legacy. An executive with a concentrated position may be constrained in terms of how much of the stock can be sold at any given moment. Moreover, her risk may be exponential—if the company fails, she not only loses her investment, but her job, too. By the same token, she may be relatively comfortable with a higher degree of concentration than normal, and feel compelled to hold onto shares out of loyalty, or a perception thereof. In contrast, family members with undue concentration may have no such bond and be more concerned about achieving diversification. In many cases, taxes will be a key issue, as concentrated positions often carry a low cost basis.

Regardless of personal situation, a concentrated position should not be met with complacency. History is littered with once-prominent companies that took a turn for the worse. This includes not only notorious failures such as Enron or WorldCom, but also companies with strategic flaws (AOL Time Warner), difficult fundamental environments (the energy sector in 2015) or whose overvalued stocks simply fell back to earth (the ‘70s “Nifty 50”). Leaving aside such examples, even prosperous single stocks tend to be very volatile compared to diversified portfolios, presenting a challenge for investors looking for a smoother ride.

Depending on the situation, the approaches to dealing with concentration risk may vary, but the basic building-block strategies are fairly consistent.

Basic Approaches

Sell the stock. Sometimes the simplest choice is the right one. A stock position may simply be too large a percentage of your overall net worth, or you may have a significant liquidity need. Obviously, selling all or a large portion of the stock position can come with a significant tax cost given the current top capital gains tax rate of 20% (or 23.8% including the surcharge on investment income for high earners). Sometimes investors choose to sell gradually, for example over two or three years. This extends the period of exposure, but also is a way to spread out the realization and payment of taxes and dollar-cost-average out of the position.

Build a completion portfolio. If you are unable or unwilling to sell a position, it may be prudent to avoid compounding your exposure with securities that may duplicate your risk. If your stock is in a large U.S. health care company, for example, you may consider otherwise underweighting that sector and large caps in general.

Options and Forwards

Buy a put. This strategy gives you the right to sell your stock at a given exercise price (typically lower than the current market price), providing you with downside protection. It can be an expensive approach, and thus may only be an option for use on a temporary basis (for example, if you are selling in stages, as referenced above).

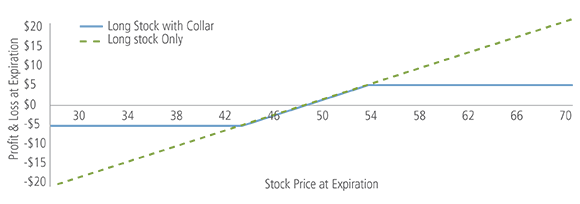

Create a ‘zero-cost’ collar. Here you buy the protective put, but finance it with the sale of a call on the same stock. The call gives someone else the right to buy the stock at a particular price, usually above market value. If the stock stays between the call and put option prices, nothing happens. If it moves above that range, the stock would likely be called and you would then have to sell. If it slips below it, you have the option to sell. Essentially, you limit your upside in exchange for some downside protection at a lower cost.

Hypothetical: Equity Position with ‘Zero-Cost’ Collar

- Investor owns shares with current market price of $50

- Purchases six-month put option with strike price of $45 (10% below)

- Sells six-month call option with a strike price of $55 (10% above)

- Premium from call offsets cost of put

For illustrative purposes only.

Write a covered call. This technique is less about downside protection than income generation. By repeating the process over time, you are able to create an income stream from a position that you might otherwise prefer to sell, and partially offset potential declines. However, with a covered call, both downside protection and upside are limited.

Prepaid variable forwards can help liquefy a position while deferring a sale for tax purposes. These forward contracts provide the investor with an upfront payment of generally 75 – 90% of the shares’ current value against their delivery at a later date. The forwards offer protection from a drop in the stock price below an agreed “floor” price while allowing participation in the upside up to a higher price, or “cap.” If desired, you can use the proceeds to invest in a diversified portfolio.

Other Approaches

Exchange funds allow you to pool your concentrated stock in a fund with other investors’ stocks, thus creating a more diversified portfolio, which is run by a professional manager. Once the fund reaches its target size and portfolio composition, it closes and each investor receives a pro-rata share, which can be redeemed after a set period without penalty (usually seven years). The technique helps to dampen your concentration risk while deferring a tax event. It is important to note that at least 20% of the exchange fund must be held in illiquid investments, which may require you to contribute cash in addition to your stock.1

Rule 10b5-1 trading plans. Corporate insiders can prearrange the sale of stocks under carefully outlined conditions regardless of whether the sales take place during a blackout or other restricted period. Such plans, which must be adopted at a time when the insider is not in possession of material, nonpublic information, provide liquidity as well as an affirmative defense against allegations of insider trading, and a potential reduction in market impact from an insider sale.

Estate Planning and Concentrated Stock

Beyond these strategies, it can be important to integrate the stock into your estate planning. Concentrated stock positions often carry a low cost basis for tax purposes, which may inhibit your inclination to sell. However, at death current U.S. tax law provides that stock held in your name receives a step-up in basis, which can reduce or eliminate the capital gains tax upon sale. This means that, depending on your age and other circumstances, the benefits of holding onto that stock may outweigh the risks. As such, certain value preservation approaches noted above, like a zero-cost collar, may be considered to bridge that gap.

Assuming you are charitably inclined, donating appreciated stock can be highly tax-efficient, as you can generally take a deduction for the stock’s full market value (up to 50% or 30% of AGI depending on the type of organization receiving the donation) regardless of the cost basis. Another popular technique is to donate the shares to a charitable remainder trust (CRT). The CRT sells the stock and reinvests in a portfolio of diversified or income-producing assets, which is designed to provide you with regular distributions for a set period of time or until death, and leave the charity with the remainder. You receive an immediate tax deduction for the value of the remainder interest, subject to restrictions based on your adjusted gross income (AGI). If your deduction in year one is limited due to your AGI, you can carry over the excess into future years for a period not to exceed five years. Depending on your goals, a low interest rate environment may be less conducive to this strategy.

Customization Is Key

Investors come to concentration from multiple routes, whether through executive compensation, inheritance or portfolio strategy. Moreover, their personal circumstances may be quite different. Some may depend heavily on the value of the position, while others may be more motivated by legacy issues. It’s essential to put in place a plan that accounts for the concentrated position in the context of your specific situation to increase the likelihood that you achieve your objectives.